Impropriety in monitoring elections

Wernick shouldn’t be monitoring election fairness, Lorne Gunter says

I am against the federal government’s Critical Election Incident Public Protocol (CEIPP) in principle. But given the up-to-his-eyeballs involvement of Clerk of the Privy Council Michael Wernick in the prime minister’s efforts to pressure former Attorney General Jody Wilson-Raybould into ending the criminal prosecution of SNC-Lavalin, I now have very practical objections to the CEIPP, too.

In early February, Democratic Institutions Minister Karina Gould announced that during this fall’s federal election five senior civil servants will monitor the Internet for any sign of foreign meddling in our campaign.

Gould insisted this was not about “refereeing the election.” Rather, the CEIPP was about “alerting Canadians of an incident that jeopardizes their rights to a free and fair election.”

Okay, some giant hack of voting results that changed the outcome in several ridings might qualify, but Gould instead said the Liberals’ main concern was stopping “fake news” and “orchestrated disinformation campaigns.”

That’s a whole different kettle of fish. That sounds like an attempt to monitor the issues voters can and cannot see during an election.

That’s not a conspiratorial fear on my part. Canadian law already makes it very difficult for any group other than registered political parties to advertise their views during a campaign. Since the internet offers these “third parties” a powerful new way to get around the politicians’ advertising monopoly, is it that hard to believe the government would try to regulate Internet and social media in the name of “fairness” and use “fake news” as their excuse?

The key to the CEIPP’s objectivity, then, is who sits on it. And that is where my practical concern comes in.

I was already worried about the objectivity of Clerk of the Privy Council Michael Wernick before Wilson-Raybould’s testimony this week at the Commons Justice committee.

In his own testimony last week, Wernick exclaimed that he was “deeply concerned about my country now, its politics, and where it’s headed.”

His main concern was “the rising tides of incitements to violence when people use terms like ‘treason’ and ‘traitor’,” directed at public figures such as the prime minister. Wernick added, “Those are the words that lead to assassination.”

No one on the committee had asked him about this. It seemed evident he was simply trying to distract the committee from it real purpose, namely SNC-Lavalin.

Wernick did not say specifically that he was worried about the “yellow vests” who had driven their oilfield service trucks from western Canada to Ottawa that week. But given that some of them had displayed placards with the words “traitor” and “treason” on them, it was not hard to figure out who Wernick meant.

And if he cannot distinguish between frustrated people letting off steam by using exaggeration and real conspirators plotting to commit crimes, then Wernick has no business being named as one of the five impartial monitors of our upcoming federal campaign.

He also has no business being put in charge of election fairness if, in his judgement, a bunch of oil patch workers are a greater threat to Canadian democracy than an orchestrated effort by the Prime Minister’s Office to undermine our federal justice system on behalf of a Liberal-friendly corporation and on behalf of Liberal party re-election hopes.

Worse yet, since Wernick’s own credibility-shattering testimony, Canadians have heard from Wilson-Raybould herself. If her testimony is accurate, Wernick is also guilty of serving as a surrogate for the PM in pressuring Wilson-Raybould to get a deal done for SNC or face personal political consequences (such as being demoted in cabinet, which she was).

Wernick is supposed to be entirely non-partisan. Entirely. Given his entanglement in the SNC affair, he probably shouldn’t keep his main job, but he definitely can’t keep his post as an impartial monitor of this fall’s campaign.

****************************************************

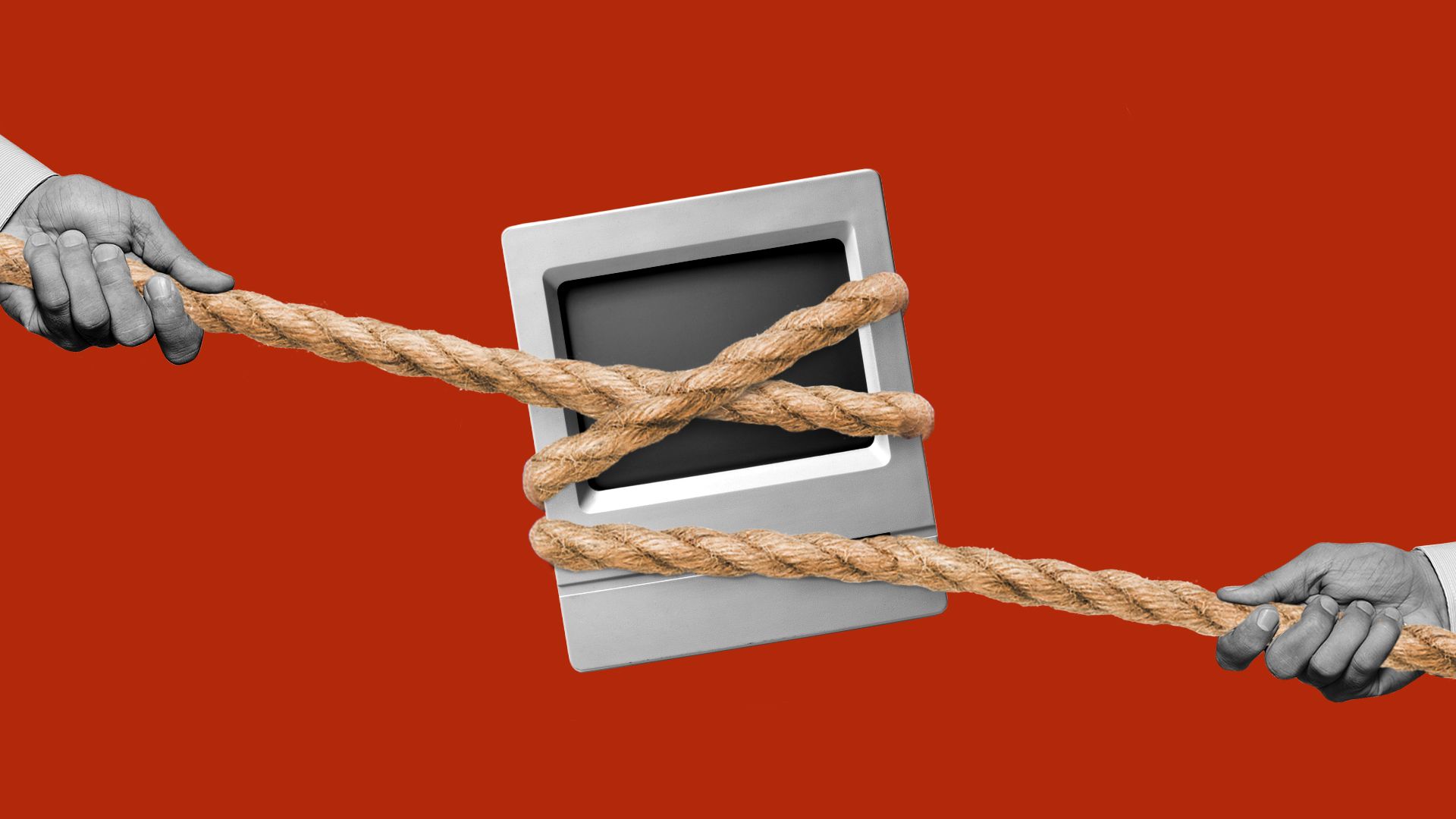

A global reckoning around the future of the internet is underway as autocratic regimes look to censor the internet in their countries, and races to develop new internet technologies, such as blockchain and 5G, heat up between the U.S. and China.

Why it matters: The next version of the internet could be split between countries that embrace an open web and isolationists that don't. It could also be fractured by different technologies that could fundamentally change the interconnected nature of the network and limit who can do business where.

A world and web divided

A global reckoning around the future of the internet is underway as autocratic regimes look to censor the internet in their countries, and races to develop new internet technologies, such as blockchain and 5G, heat up between the U.S. and China.

Why it matters: The next version of the internet could be split between countries that embrace an open web and isolationists that don't. It could also be fractured by different technologies that could fundamentally change the interconnected nature of the network and limit who can do business where.

.png)